Incorporated in 1810, the city of Hamilton was a town on the forefront of the Industrial Revolution. City leaders of the 19th Century harnessed the power of the Great Miami River to power a new machine-driven economy, and industrial magnates built sprawling factories producing paper, vaults, safes, locomotives, and machine tools. During the world wars, Hamilton factories churned out engines, tank turrets, and gun lathes.

It was a great run, but by the later years of the 20th Century, as the manufacturing economy in the U.S. waned, Hamilton became an emblem of the Rust Belt. Once-mighty powerhouses like Champion Paper and Mosler Safe shrunk and eventually departed, leaving shells of factories in their wake.

Hamilton acquired a reputation, fairly or unfairly, as a town whose best days were behind it. Growth, both in population and business, eluded it. It became so frustrating that in the late 1980s its mayor, following the recommendation of a marketing expert, decided to append an exclamation point to the city’s name in an effort to generate attention. The new name (Hamilton!) never really caught on, and mapmakers rejected it. Although it did result in national, even international, publicity for the city, much of the attention was disparaging.

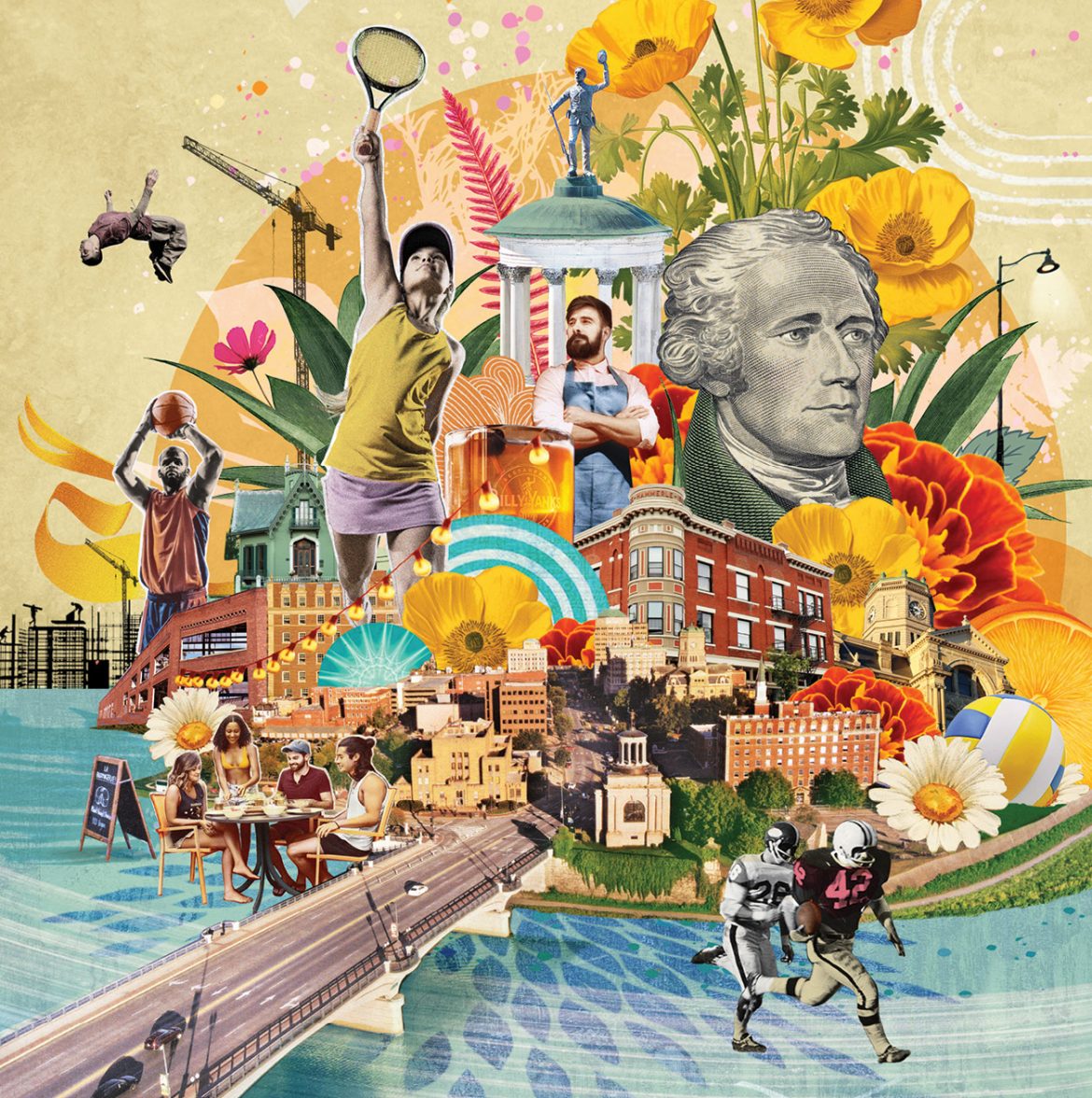

These days, there’s no need for superfluous punctuation to get the world’s attention. Just in the last few years, hundreds of millions of dollars worth of new developments in office, industrial, housing, and retail have been built or planned. Some of Hamilton’s sprawling old industrial sites have been redeveloped, rehabilitated, or purchased with plans to build new commercial and residential properties. That, in turn, has sparked new developments in the hospitality business, as additional hotels and restaurants are in the offing.

In the span of a few years, Hamilton’s identity has shifted from Rust Belt Burg to Renaissance City. “There’s just a lot of momentum,” says Bob Hoying, a Dublin, Ohio developer whose company is planning a $150-million mixed-use project on an old manufacturing site along the Great Miami River.

Downtown Hamilton, once the site of a single hotel, is now expecting six new ones, which city officials expect will be built over the next three to five years. On the food and drink scene, the Cincinnati-based owners of Incline Public House in East Price Hill and Jefferson Social downtown opened Billy Yanks in 2021 and are planning two new concepts. The city’s first brewpub, Municipal Brew Works, is expanding, and two others have either opened or are on the way.

Major new mixed-use developments are on the drawing board. Crawford Hoying, the Dublin-based company that took control of The Banks development on the Cincinnati riverfront last year, is planning a Banks-scale project—including housing, hotels, and retail—on 18 acres along the Great Miami. In August, the company completed its purchase of the property that’s now the site of a scrap recycler and was once part of Champion Paper’s operations.

The spark for much of Hamilton’s positive momentum is a $165-million development called Spooky Nook Sports, which its owners say is the largest indoor sports facility in the U.S. The Pennsylvania-based owner bought 40 acres of land and deteriorating buildings once belonging to Champion Paper and transformed it into a complex that can host sports tournaments ranging from basketball to lacrosse to pickleball to soccer and beyond. There’s a total of 1.2 million square feet under roof, the equivalent of seven or eight Kroger superstores.

“It’s why we’re seeing an acceleration of development,” says Hamilton City Manager Joshua Smith. “We were already seeing an upward trend in restaurants and unique retail, but Spooky Nook has certainly moved that along a little bit faster.”

The main Spooky Nook facility is a former paper mill that dates to the 19th Century and has been rehabilitated under historic preservation guidelines, with its brick shell and massive supporting beams retained and its long steel windows restored. The sports facilities opened for business in January. Youth sports is the main attraction, but far from the only draw. A hotel in the same building, the 233-room Warehouse Hotel, opened in 2022, and an expansive fitness center opened last year across the street in a newly built facility.

Beyond sports, Spooky Nook is also a significant addition to the region’s conference and meetings business. A 600,000-square-foot conference center opened in 2022, a meeting space far bigger than the Sharonville Convention Center and almost on par with the available space at downtown’s Duke Energy Convention Center. In August, the sales force of a large national company convened there and used the sports facilities for team-building exercises, says Scott Rodgers, Spooky Nook’s general manager.

There are a restaurant, a brewpub, touristy retail, and more on the way. Spooky Nook’s owners have said they expect more than a million visitors a year when the facility hits its stride. Many of them will come for events like the Under Armour Association girls basketball tournament that was held over four days in July. High-school age club teams from around the country brought more than 15,000 players, parents, siblings, friends, and relatives to converge on North B Street in Hamilton over that long weekend, Rodgers says.

Spooky Nook will capitalize on the big business of youth sports and sports tourism. The sector rebounded quickly after the COVID-19 shutdown, and in 2021 it generated $39.7 billion across the U.S. in direct spending on tournaments, hotels, restaurants, merchandise, and other recreation, according to a report by the Sports Events and Tourism Association. That spending in turn generated a total economic impact of $91.8 billion.

Spooky Nook’s Hamilton venue is modeled after the company’s smaller 700,000-square-foot site in Manheim, Pennsylvania (between Harrisburg and Lancaster). Sam Beiler opened it in 2013 after he and his wife traveled far and wide attending their daughter’s volleyball matches across the country.

Beiler owned an Auntie Anne’s pretzel franchise in Pennsylvania, and when he retired the idea of building a new and improved volleyball center came to him. He started searching for abandoned warehouses near their home in southeastern Pennsylvania for a suitable site and eventually found one on Spooky Nook Road in Manheim. He adopted the street name for the new sports facility.

Around the same time in Hamilton, the last vestiges of the once mighty paper industry closed. By 2012, Hamilton was without a paper mill for the first time in 164 years, as the operations once owned by Champion and Beckett Paper both closed that year. Plans moved forward to auction the Champion property along the river, but Smith got wind of a real estate investor’s plan to turn the historic mill on 45 riverfront acres into a cold-storage facility. “I went back to city council and said, We absolutely cannot let that happen,” he says.

On Smith’s recommendation, city council made the decision to buy the buildings and the property for $400,000. “That was the critical thing,” he says. “We had to control our future.”

But what to do with it? That’s where a bit of serendipity came in. During an auction of the mill’s machinery and equipment, Smith encountered Moses Glick, an Amish entrepreneur from Pennsylvania who bought and sold surplus industrial and farm equipment. Glick eventually bought not just the old equipment but the mill and the real estate at a good price with the understanding that he’d make improvements, most notably taking care of environmental issues that had accumulated over 150-plus years of papermaking.

During trips to Hamilton to inspect his new purchase, Glick and his vice president of operations, Mark Frank, would have dinners with Smith. Frank kept talking about a big new sports complex near their homes in Pennsylvania called Spooky Nook. “He said, That’s what we need to turn this into,” Smith recalls.

At Frank’s urging, Smith and other city leaders took a field trip to visit the original Spooky Nook. Like Glick, Nook owner Beiler was raised Amish. During the field trip, the two of them began talking in a language Smith didn’t understand but believes was Pennsylvania Dutch, the German dialect spoken by Amish. The upshot of the trip and the conversation was that Beiler agreed to visit Hamilton to tour the Champion site and possibly serve as a consultant on its redevelopment. He liked it so much he bought the property.

“He fell in love with the city and fell in love with the site,” says Smith. “That was right around 2016, and Sam has been working on the project ever since.”

The indoor sports facility opened in January and features 46 volleyball courts, 28 basketball courts, pickleball courts, indoor and outdoor turf fields for soccer, football, flag football, lacrosse, field hockey, a 200-meter indoor track, a 65,000-square-foot fitness center, and a climbing center. A pickleball tournament is scheduled for October with brackets for boys, girls, men, women, and mixed doubles. In the fall, a youth basketball tournament organized by MADE Hoops is expected to bring in about 5,000 people.

These kinds of events often are mini-vacations for families that need places to stay and dine for several days. Spooky Nook’s onsite hotel can accommodate only so much. During a basketball tournament over the summer, families had to search as far away as Northern Kentucky to find lodging, a good 45-minute drive from Hamilton, Smith says.

As Spooky Nook’s event calendar fills up, the demand is certain to grow. “It’s currently just in its first year of operation,” says Smith. “It will bring more and more people into town, which provides an opportunity to capture a lot of that hotel traffic.”

Spooky Nook’s arrival helps explain the remarkable and sudden interest in hotel building in Hamilton’s downtown core. As recently as a few years ago, only one first-class hotel was operating in the city. Today, developers are scrambling to take advantage of Hamilton’s historic structures and transform them into upscale hospitality.

A development team associated with Vision Realty Group of Northern Kentucky is redeveloping the former Anthony Wayne Hotel—situated across the way from Hamilton’s landmark Soldiers, Sailors, and Pioneers Monument—into a 54-room Hilton brand to be called the Well House Hotel. The 100-year-old, seven-story building was Hamilton’s showcase hotel for decades, but closed and was sold at a sheriff ’s sale in 1964 and then converted into senior apartments. The proposed $16-million hotel development is being undertaken with the help of state historic preservation tax credits and a grant and loan from the city.

In June, two out-of-town developers announced a $48-million plan to convert a former city building on High Street into a hotel. The historic Art Deco structure was built as a New Deal project in 1936 and housed Hamilton’s government offices until 2000. It’s now the site of Municipal Brew Works, which opened in 2016. Under the new plan, the brewpub will expand and developers will build a neighboring four-story addition with 100 rooms to bring the room total to 159. The hotel brand could be Hilton, Hyatt, or Marriott, developers say, and open in the fourth quarter of 2026. That project is proposed by Utah-based Acumen Development and Indiana-based Spectrum Investment Group.

Dining options are also expanding. In 2020, Cafeo Hospitality Group opened Billy Yanks restaurant on Main Street in a 19th-Century building that had been vacant. Cafeo also runs Incline Public House and Somm Wine Bar in East Price Hill and Jefferson Social in downtown Cincinnati, and Smith says the company is planning two more restaurant concepts in Hamilton. Blue Ash-based Fretboard Brewing opened its second location in downtown Hamilton in 2019.

By far, the biggest plans outside of Spooky Nook come from Crawford Hoying. In August, the company closed on the purchase of 18 acres now occupied by a scrap and recycling operation. What it’s planning rivals the scale of Spooky Nook, which is directly across the Great Miami from the new development site.

Crawford Hoying plans $150 million in new construction in three phases over more than 10 years. Although the company says plans may evolve, the first phase is slated to include a 120-room hotel, 176 apartments, six townhomes, and 5,000 square feet of retail space.

The recycling company has 18 months to move its operations from the site. The site was once part of Champion Paper’s operations, and there are some century-old structures the developer will assess to see if they can be adapted, says Hoying. “We love the challenge of redeveloping sites where we can keep skin,” he says. “There’s just some beautiful old brick buildings and facades that we would love to keep with some of our redevelopment as we look at building out the bulk of the site.”

The city is providing a $3 million forgivable loan, and its agreement calls for the first $50 million phase of development to be finished by December 2026. The second $50 million phase is to be finished by 2031, and the last $50 million portion by 2036. “We want to go as fast as the market will allow us,” Hoying says. “We certainly see the possibility that this could move much quicker.”

He says his company’s investment is linked to the physical location of the site on the Great Miami River; its proximity to German Village, a nine-block historic residential district just southwest of the site; and the draw of the Spooky Nook development across the river. “This really is a perfect site for what we do,” he says.

While sports, hotels, restaurants, and brewpubs get the attention, Smith says he’s still focused on what made Hamilton the city it is today: manufacturing. The city’s main source of revenue is income taxes, and good-paying jobs bring in more tax dollars to fund city services. “Our number one objective is always going to be jobs, because that’s what pays the bills,” he says. “That’s what gets the trash picked up and what lets the medic unit roll out to someone in need and the police cruiser respond to a car accident.”

One of the fastest-growing manufacturers is indoor vertical farming company 80 Acres Farms, which operates two indoor growing facilities in Hamilton. The company also has its headquarters there.

City leaders have also courted foreign companies. Last year, Spain-based Saica Group began production of corrugated packaging at a 360,000-square-foot facility in an industrial park southeast of downtown. Italy-based machine tool maker Salvagnini maintains its North American headquarters in Hamilton, where it’s expanded in recent years. Paris-based Valeo supplies heating and air conditioning systems to automakers around the country from its Hamilton location. Synergy Flavors, an Irish maker of extracts for the food and beverage industry, operates a plant in Hamilton that produces coffee and tea flavorings.

“We go after advanced manufacturing very aggressively,” Smith says. “The more diverse our local economy is, the more resilient it is.”

One of Smith’s first challenges as city manager was to try changing Hamilton’s reputation so companies would consider locating there. “A lot of our early strategies were really about placemaking and about changing the impression of Hamilton for people coming into the community,” he says.

He recalls a conversation with Claude Davis, the former CEO and current chairman of First Financial Bancorp. After Smith was hired, the two drove around town as Davis related how the bank had moved jobs out of Hamilton because it was so difficult to recruit talent. “A lot of what he said really resonated with me,” says Smith.

First Financial traces its roots to its 1863 founding in Hamilton, but in 2008 the bank moved its corporate headquarters to Cincinnati. “Having the corporate center in Cincinnati is expected to enhance the company’s opportunities to attract and retain talented associates who will help to grow the business,” the company said in its announcement of the move.

Other companies made similar moves out of town. Mercy Health, which opened the first hospital in Butler County in Hamilton in 1892, closed the hospital in 2001 and focused on expanding its presence in the neighboring city of Fairfield. Ohio Casualty, an insurance company founded in the city in 1919, employed thousands of Hamiltonians over the years. It also moved to Fairfield in 2010 after its purchase by Liberty Mutual.

While those losses stung, the experience led to a reckoning and eventually to the creation of a plan to reverse the tide when Smith was hired in 2010. “To me, attracting jobs is a function of placemaking,” he says. “You have to have a community that people want to be in so businesses can attract the workforce necessary to run an operation.”

A little more than 10 years later, the results speak for themselves.