It’s never been particularly remarkable for a person growing up in the Cincinnati region to leave home to attend a college or university and then choose to build a career elsewhere. Parents have seen their children head out for “the big city” over and over again.

These days, though, retaining graduates and attracting new talent have become economic development priorities across the Midwest, with a special focus on building a pipeline of highly skilled workers and encouraging entrepreneurs. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced a host of new wrinkles—including remote work and a broader recognition of the Midwest’s attractiveness for tech-driven manufacturing and strong startup culture—that are actually contributing to a return of talent and investment to U.S. heartland cities.

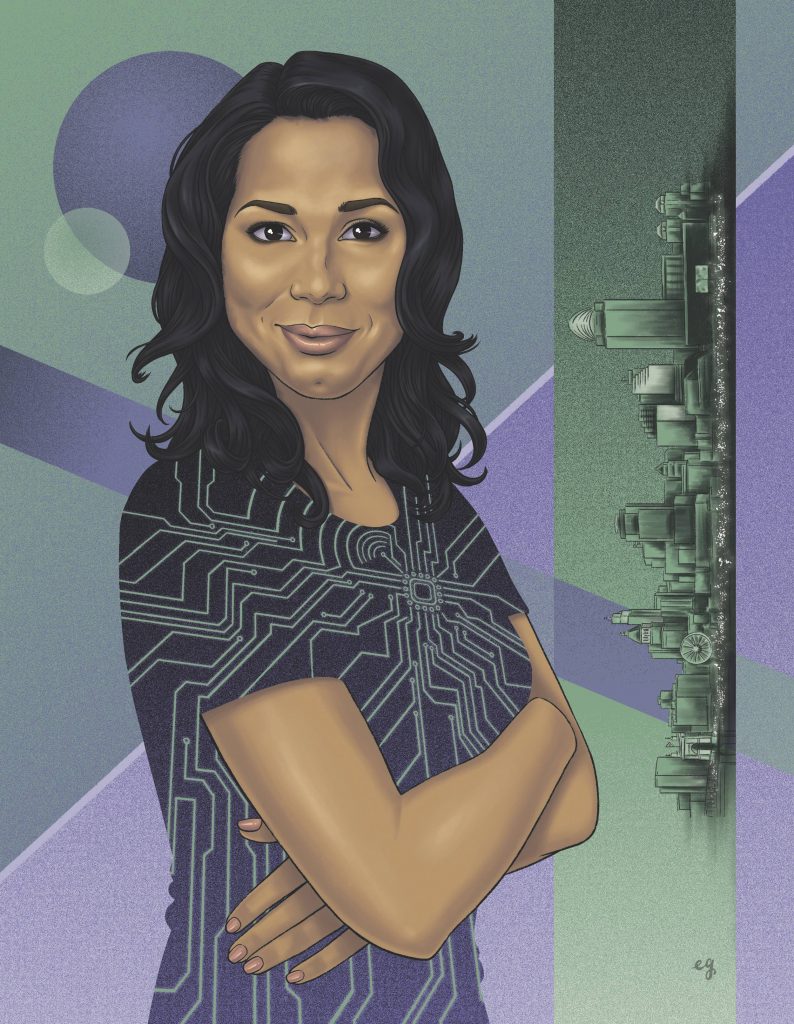

Tech entrepreneur and venture capitalist Candice Matthews Brackeen, founder and executive director of Lightship Foundation, is working at the intersection of talent retention and pandemic responses. She’s hoping to ensure that both pandemic recovery resources and new investment flowing into the region’s innovation ecosystem equitably support Black-owned startups and other underrepresented communities.

Brackeen has found numerous partners in this region and honed her purpose of empowering diverse innovation ecosystems here and across the nation. She credits her University of Cincinnati economics degree work with exposing her to opportunities within the local business community. From there, she developed an app for which she raised venture and angel capital, launched Hillman Accelerator, coaxed a cohort of fellow Cincinnati “Black techies” to regularly convene, and launched a $50 million venture capital fund with her husband and fellow startup founder, Brian.

Brackeen’s profile is steadily rising. She serves as a member of the Cincinnati Innovation District’s advisory council along with Ohio Lt. Gov. Jon Husted, retired Procter & Gamble CEO David Taylor, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center CEO Steve Davis, REDI Cincinnati CEO Kimm Lauterbach, CincyTech CEO Mike Venerable, University of Cincinnati President Neville Pinto, and others. The district is currently anchored by the 1819 Innovation Hub and two soon-to-open Digital Futures buildings, as well as by a mission to serve as the region’s primary driver for talent attraction and development. (See more about the district’s uptown facilities on page 56.)

In March, Lightship Foundation announced it had acquired Black Tech Week, a five-day conference with thousands of attendees annually. Held in Miami, Florida, for the past seven years, including two virtually, Black Tech Week happens in person in Cincinnati July 18-22. The conference intentionally is a bookend event to the Procter & Gamble-sponsored Cincinnati Music Festival July 21-23 at Paul Brown Stadium, which usually attracts more than 70,000 visitors. Janet Jackson is its Saturday night headliner.

Minority-owned businesses in all sectors have been disproportionately impacted by COVID. Brackeen, 44, says that while there’s a sense of “hope and optimism” among Black entrepreneurs and other founders historically underrepresented, “the numbers have slid backwards in the last two years. If 1 percent of Black founders and 6 percent of women and people of color before the pandemic were getting venture capital, those numbers are even less at this point,” she says. “Our local region has spent time saying, OK, we recognize that rescue plan dollars didn’t make it to who needed it. We recognize that lots of small businesses closed and many of them were historically disadvantaged. Now let’s try to course correct some of those things. So I’m hopeful that if we pull together we can go in and fix disparities as we see them.”

Candice Matthews and Brian Brackeen rekindled a friendship at Black Tech Week in 2018, so the event is near and dear to their hearts. They married in 2019 and a year later announced that a new VC fund, Lightship Capital, would raise $50 million to invest in underrepresented founders in the Midwest. That same year, The Wall Street Journal named Candice Matthews Brackeen to its top 10 list of women VCs.

She says that although most venture capital in this country gets invested in San Francisco, New York City, and Boston, there are plenty of great opportunities in Cincinnati and across the Midwest. “I feel that intelligence is distributed equitably, but opportunity isn’t,” she says.

“I am just attacking a market failure with Lightship Capital,” Brackeen said in late June at REDI Cincinnati’s board meeting. “The market has failed our area, and it’s failed the demographic of people we serve. I’ve gone back to my economics background and said, How do I serve a niche that no one else is working on? I’m able to find companies at a really great valuation, invest in them, and spend time helping them grow and thrive and drive them up toward a higher valuation. If I look at my peers who have invested at inflated valuations, they’re struggling to figure out what they’re going to do. Our portfolio is tracking quite well.”

SoLo Funds is one success story Brackeen cites from her work through Hillman Accelerator, which she launched with former Cincinnati Bengals player Dhani Jones. The Black-owned lending platform helps users secure small-dollar, short-term loans as an alternative to traditional banking or risky payday lenders.

When Brackeen moved from her hometown in Toledo to study at UC, her intention was to forge a career path in entrepreneurship. Her connection to UC continues to shape her journey; she hasn’t ventured too far outside of the institution’s force field. “A group of UC professors helped me enjoy a discipline that I would have never gotten involved with had it not been for a few people saying, You should apply for this scholarship,” she says. “It was through that (economics) fellowship that I was able to see what was happening in Cincinnati.”

Lightship Foundation will relocate its office later this year from the 1819 Hub to The Beacon, owned by UC and located at 121 East McMillan Street. UC and JobsOhio, the state’s private economic development organization, are among the project’s funders. The Beacon represents a meaningful expansion of the Cincinnati Innovation District’s footprint.

Maurice E. Coffey II, a senior P&G marketing executive who spends the majority of his professional time “on loan,” has served as a full-time executive-in-residence with Cintrifuse since 2017 while also leading the board at Lightship Foundation. “I have been with Candice since 2018 when she was one of the founders of Hillman Accelerator,” he says. “I sat down with her and her team and came up with a five-year plan from my P&G training. They looked at me like I was crazy and said, Everything is exactly what we need, but we’re startups. We don’t have five years. They took that plan and have squeezed into the last two or three years what normally would have taken Procter & Gamble many years to roll out.”

Brackeen says Cincinnati’s culture enables entrepreneurship and innovation growth. “It’s kind of wild that C-suite executives will have coffee with you here,” she says. “Folks give you a level of grace and patience you might not get elsewhere. I’ve been allowed to grow personally and professionally. When I’d speak with business leaders about making the local tech ecosystem more inclusive, they did truly believe in their heart of hearts that it already was. And when I toldthem it wasn’t, they listened. The difference here is that I was taken seriously. I couldn’t have grown Lightship Capital anywhere else.”

Lightship Foundation is a member of the new Lincoln & Gilbert consortium deploying funds to help double the number of Cincinnati’s minority-owned business enterprises in five years. Led by the African American Chamber, the Minority Business Accelerator, the Urban League of Greater Southwestern Ohio, Mortar, and the city of Cincinnati, Lincoln & Gilbert is providing loans and technical assistant primarily to Black entrepreneurs. The initiative is named for the intersection of Lincoln and Gilbert avenues in Walnut Hills, a hub of the neighborhood’s historic Black business district.

David Adams, UC’s chief innovation officer and executive director of the Cincinnati Innovation District, wrote in The Wall Street Journal in January that Intel’s planned $20 billion chip factories near Columbus “points to a broader shift away from the country’s predominantly bicoastal tech economy.” In March, the Brookings Institute released research supporting that premise, citing evidence of the rise of tech jobs in atypical cities across the U.S. heartland and beyond. Cincinnati was named as one of 36 metro regions where tech employment grew significantly in 2020 compared to pre-pandemic years.

“In today’s knowledge economy, talent is the economic driver—it’s 10 times more valuable than land,” Adams wrote, saying that Intel’s decision was partly due to the work under way across Ohio to build the workforce of the future. “That’s a fundamental shift in the economic development discussion. Are there states willing to build the workforce that’s needed?”

Brackeen says the public sector’s financial support and championing are critical for cities, states, and regions to attract and retain talent, noting state government’s role in recruiting Intel. “If we think about Silicon Valley, there would be no chips without federal grants,” she says. “The role of government is validation and being a convener. It fixes things when private markets don’t or can’t.”

Cincinnati Mayor Aftab Pureval says the city is investing to enable more tech-enabled manufacturing and follow-on investments spurred by the Intel announcement. “I’m convinced that we will see an inward migration of talent because of the rising costs of living on the coast and because of climate change that continues to erode our coastline,” he says. “We’re already seeing the effects of the multibillion-dollar investment from Intel into Central Ohio. One of the key reasons they chose that area is because of Ohio’s climate resiliency and access to water.”

In addition to the city’s investments, particularly around Black Tech Week, Pureval says he’s trying to leverage the Intel investment by partnering with REDI Cincinnati and The Port to invest $7 million in the city’s budget for development site readiness to encourage and grow high-tech manufacturing plants, particularly along the I-75 corridor. The city is also investing $5 million in the Lincoln & Gilbert fund. “At every level of the Black ecosystem, from tech to traditional, the city is making investments,” he says. “But the biggest thing we can do as a city is to be a destination for young, diverse talent. That means creating dense, diverse neighborhoods that are walkable, where people who are my age and look like me want to live.”

Pureval says his administration is “laser focused” on growing the city’s economy with racial equity as a centerpiece. “Racial equity is a buzzword that gets thrown around, but the way I define it is with one word: ownership,” he says. “Black ownership of homes, Black ownership of neighborhoods, and Black ownership of businesses. Data shows that Black businesses fail to start or to grow because of a lack of access to capital, to talent, and to infrastructure. We’ve made specific and bold investments in our budget to accomplish those goals, specifically helping fund Candice’s efforts through the Lightship Foundation to bring Black Tech Week to Cincinnati.”

A recent Brookings report, Black-Owned Businesses in U.S. Cities, attempts to quantify the revenue, jobs, and wage gains for Black residents of U.S. cities if the percentage of Black-owned businesses was on par with the metro area’s Black population share. There are 732 Black-owned businesses in the Cincinnati region, accounting for 2 percent of all employer businesses. If Black businesses accounted for 13.8 percent of employer firms, equivalent to our Black population, there would be 4,398 more Black-owned businesses here.

An April Brookings case study, Cincinnati Cited As a Model for Inclusive Economic Growth, highlights positive steps being taken to build inclusive economies and includes the Cincinnati Innovation District as a national model. P&G’s Coffey agrees with the positive outlook, saying the work underway to build a diverse tech ecosystem across the region makes it difficult for companies to say they can’t find diverse vendors and companies to invest in.

“The data show that less than 2 percent of VC funding goes to anyone other than white men,” says Coffey. “But I think that’s being accepted and addressed by those in power here. The excuse in the past was, But we can’t find quality workers or We can’t find the right types of businesses to invest in. Local corporations, foundations, and funders immediately accepted the challenge of Cincinnati hosting Black Tech Week, so we were able to hit almost all of our fundraising goals within 45 days.”

Brackeen is pleased that regional companies and foundations got on board quickly to support Black Tech Week. “I think we’ve finally gotten to a point in Cincinnati’s history that we’re funding entrepreneurship to support people to get out of the places they were instead of putting philanthropic money into dealing with issues of poverty,” she says. “Economies grow when you give folks other ways. I think that’s what I’m most proud of.”

Pureval says that Black Tech Week is emblematic of the current state of Cincinnati and its future. “We are young, diverse, bold, and ambitious,” he says. “We’ve got that Cincinnati swagger, not unlike our Bengals, and we’re not just happy to be on the national stage. We belong here. The fact that we’re taking Black Tech Week from Miami and putting it in Cincinnati says everything about what we value, who we are, and what we believe our future to be.”

Entrepreneurial spirit and gumption is alive and well in Cincinnati’s African-American community, Coffey explains. “It always has been that way, despite the structural and systemic racial barriers of education, employment, and wealth-creation. There is now more light being directed on these barriers, and so more institutions, both private and public, are committing real resources to address them.”