The 1960s were a turbulent time. Otto Budig Jr. was flying B-52 bombers from the U.S. air base in Guam to targets in Vietnam. His brother, George, was an administrator at a big college in the Southeast. The world was changing at breakneck speed.

Back home in Cincinnati, their father, Otto Sr., was running the trucking business he’d founded in 1949 on borrowed money and two rented trucks. As founders tend to do, he had thrown everything into the business, which had teetered on the brink of failure in the early days. Now it was growing so fast he had to do something out of character: Ask for help.

“Dad called us and said his business was getting so large he’d have to either bring someone in to replace him or sell it,” Otto Jr., the elder son, recalls. He turned first to his sons. “I’m offering you an opportunity to come in,” he told them.

It was an offer, not a demand, and it was a tough choice. Budig Jr. was 14 years into a career in the Air Force, having flown in Korea and during the Cuban missile crisis and now piloting the biggest bombers the U.S. military owned. “Clearly, for me, it was the most difficult decision of my life,” Budig says today. “I was offered a challenge that neither my brother nor I had contemplated, but the offer came and we took it.”

It was a fortunate decision. Budco Group is now one of the key players in the U.S. transportation industry. Its Parsec Inc. unit is a link in the nation’s supply chain, specializing in intermodal transportation, getting freight from trucks loaded on to trains and from trains on to trucks. Its workers handle nearly half of all the intermodal traffic in the country, managing cargo for the major railroads at terminals and ports in 18 states and three Canadian provinces. Budco Group also leases semi-tractors, trailers, and other equipment and maintains extensive real estate holdings. The company employs 2,800 people.

It’s a family success story, and a relatively rare one. An oft-cited Northwestern University study found that only 13 percent of family businesses make it through three generations. That study is often interpreted to mean that most family businesses end in failure, though making it through three generations could mean a 90-year run—longer than many publicly traded giants last.

Family-owned businesses support the country’s economy, accounting for 90 percent of all businesses in North America, according to the Columbus-based Conway Center for Family Business. They create the fabric of community’s identity, they build wealth that stays local, and they cultivate neighborhood and civic pride.

In Cincinnati, the success of Budco Group has resulted in Budig Jr. becoming one of the region’s major philanthropists. Through the Otto M. Budig Family Foundation, named for his father, Budig has donated millions to the Cincinnati Symphony, Cincinnati Ballet, Cincinnati Zoo, Music Hall, local theater, and many other organizations.

Now 88, he retains the title of Budco chairman but has passed on ownership and management to the third generation, sons David and Mark and daughter Julie. A grandson, Quinn, 28, works at the company headquarters in Queensgate, putting him in line to be the fourth generation. “My greatest satisfaction is seeing that the next generation is not only doing the good job I thought it would do, but it’s expanding and is very dedicated,” Budig Jr. says.

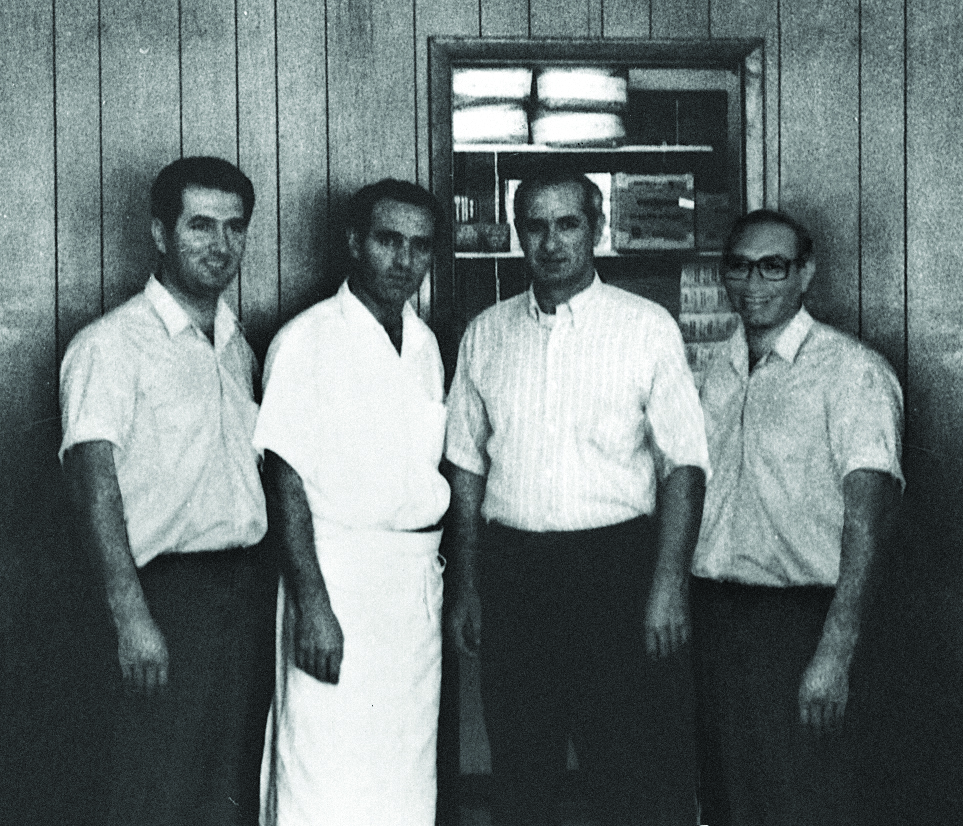

and their parents in 1963.

For any family business, long-term success over generations comes about only after working through all kinds of challenges, ranging from the kind most businesses face (competition and a changing economy) to those peculiar to families (communication, rivalry, and parochialism). Running a small business in a world where bigger is considered better is hard enough. Throw in the unpredictability of family dynamics, and the obstacles can lead to failure.

“The number 1 reason family businesses don’t succeed is lack of communication and trust,” says Carol Butler, president of the Goering Center for Family and Private Business, a nonprofit organization affiliated with the University of Cincinnati that was set up to help family-owned businesses navigate the potential pitfalls they are prone to. “When interests are no longer aligned, conflict can occur.”

The Center provides resources to help family businesses stay intact and grow, such as its Next Generation Institute and Leadership Development Institute, and roundtables with other business owners. It’s the largest university-affiliated family business center in North America by membership, says Butler.

The Center was founded in 1989 by John Goering, whose family owned a meatpacking business. While working there with his father and uncle, Goering (who passed away in February 2021 at the age of 87) witnessed discord between the two, and years later he resolved to do something about it, working with UC’s business school to establish the Center. “The whole thing was born out of conflict,” Butler says. “Out of conflict comes opportunity.”

Butler herself grew up in a family business, Butler’s Orchard in Germantown, Maryland, which is in its second generation of family ownership, with members of the third generation involved in the operation. She returns to the farm in the fall to help with the busy fall festival season. “I’m still welcomed home,” she says. “They still ask my advice.”

Photographs by Chris Von Holle

The well-known and -loved Cincinnati brand Gold Star also prospered by listening to outside advice. The restaurant chain was led by nonfamily CEOs for 25 years after the founding brothers looked outside of the family for help, though today it’s again led by a family member.

Gold Star was founded by four Daoud brothers who had emigrated from Jordan in the 1950s. They landed in Cincinnati thanks to an uncle who had arrived here from Jordan a few years earlier and suggested they could find jobs.

Basheer studied at Xavier University and began a career as an accountant. Charlie followed in 1952, finding work as a door-to-door salesman. Six years later, Frank joined them and studied business at Xavier. The final brother, Dave, arrived in 1958 and landed a job as a gardener at Spring Grove Cemetery.

Like all Cincinnatians, they learned about the city’s unique style of chili and through their church began meeting other immigrants who worked at chili parlors around town. In 1963, they heard of an opportunity to buy a restaurant in Mt. Washington called Hamburger Heaven, which sold burgers, naturally, but also came with a recipe for Cincinnati chili. They decided to take the plunge but needed to come up with $12,000 as a downpayment on the business and the two-family house next door. They only had about $1,200 together, but scraped to find the rest and went to work. Charlie managed the front of the house, Dave ran the kitchen, and Basheer handled the accounting. After returning to Jordan for a bit, Frank rejoined the business.

In the kitchen, Dave tinkered with the chili recipe. As one of the few East Side restaurants serving Cincinnati chili at the time, it became a popular customer choice, and chili sales at Hamburger Heaven more than doubled. They were going so well that by 1965 the brothers decided to drop the Hamburger Heaven name and focus on Cincinnati chili. A family elder suggested the name Gold Star.

The brothers ran the business for about 25 years before deciding they needed some help. “In order for this to work, we’ve got to let go of the wheel a little bit” is how the current CEO, Roger David, recalls the decision. They tried out a couple of non-family chief executives before finding John Sullivan, who ran Gold Star for 16 years. “That’s when they understood what it meant to be a shareholder and not an operating shareholder,” David says. “That was a learning curve for the founders.”

David, the son of co-founder Charlie Daoud, worked in Gold Star’s marketing department for about 10 years before going back to school for an MBA and then heading off to do his own thing. “It was not an easy decision,” he says. His father was deceased by then, and Roger was the oldest of his siblings. “To tell my mom that I’m leaving the family business was not an easy discussion to have,” he says. “But it allowed me to spread my wings, learn different things, and bring that expertise back to the organization.”

David spent 15 years away from the family business but remained a board member. He ran a competitor, Buffalo Wings and Rings, where he was CEO for a few years, turning around the chain and refashioning it into a family-style restaurant.

When Mike Rohrkemper retired as Gold Star CEO, David threw his hat into the ring to replace him. “They entertained the idea,” he says of his founding uncles. “They didn’t make it easy on me.”

David took over in 2015 and began realigning the Gold Star brand, redefining its core market to within 200 miles of Cincinnati, investing millions in store redesign and marketing, and going back to the future by introducing burgers to the menus in some locations.

Gold Star entered a new market in 2017 with the purchase of Tom and Chee, the small chain that serves creatively made grilled cheese sandwiches and soups. David believes the concept can be grown beyond the Greater Cincinnati market. He and his management team created a new organizational structure, GSR Brands, to be the parent organization of Gold Star and Tom and Chee and to enable other potential acquisitions.

The number of family shareholders has grown from the original four to 16, and David says half of his extended family, about 25 people, is involved in the business in some way. His years away from the family business helped his decision-making now as its chief executive, he says. “When you grow up in the business, it becomes part of you, and when something becomes part of you there’s an emotional element involved.” Those years studying and working outside the family business “helped me be a lot more strategic about the choices we’re making,” he says.

One of Cincinnati’s oldest family-owned businesses made use of outside advice from the Goering Center to ease the transition from one generation to the next. Rich Graeter came into the family ice cream business in 1989, along with cousins Chip and Bob. It wasn’t until 15 years later that the three ascended into company leadership, with Rich as CEO and Chip and Bob running significant pieces of the operation.

Graeter’s is now in its fourth generation of family leadership, but getting there wasn’t necessarily a slam dunk. Deciding who’s going to be the boss, who’s in charge of what, and exactly how this time-honored Cincinnati business would be handed down took a lot of work. “I don’t want to understate how difficult it was,” Rich Graeter says. “We had fits and starts, high points and low points. It was a fairly grueling process.”

Since 1989, Graeter’s had essentially been run by six family members: Rich’s father, Richard; Chip and Bob’s father, Louis; Aunt Kathy, sister of Richard and Louis; and the three cousins. The three put their heads together and came up with a succession plan that they presented to the older generation. It was a welcome development. “They were thrilled that we were presenting a plan together,” Rich recalls.

But executing the plan would take time and outside help. Along with the Goering Center, the Graeters hired a psychologist who specializes in the dynamics of family businesses. With help, the fathers, sons, brothers, sister, and cousins were able to see how this business, launched by Louis Graeter in 1870, was bigger than each of them. “We can accomplish more together than we can individually,” says Rich. “Once everyone comes to that realization, you can move forward.”

After the fourth generation formally took over, they continued to seek outside help. An organizational consultant was hired to help them figure out what they wanted to be. How do you stay viable in a competitive retail landscape and keep manufacturing a high-quality, high-profile product?

“We decided, number 1, that we wanted to be in business forever,” Rich recalls, saying one option that leads to the demise of many family businesses is to sell. “That was not ever going to be our goal. You run a business you want to keep forever differently than one you want to cash out.”

The cousins decided to focus on what they do best: make great ice cream. They bought out their franchisees, ending an experiment that had begun years earlier. They would stick with the French pot method started by their great-grandfather in Walnut Hills all those years ago, a technique Rich calls “an antiquated, labor-intensive, old-world process.”

Graeter’s hired an operations consultant who helped find efficiencies in the old-fashioned practice. That resulted in an uptick in production and enough capacity to try selling their wares at grocery stores, and that went so well a new plant was necessary. “We were making ice cream at the time at a plant that my great-grandmother bought in the Depression in 1934,” says Rich.

That year, Regina Graeter bought a factory in Mt. Auburn and transformed the small business from making ice cream in the back room and selling it in the front to a real manufacturer. Although times were changing and modern production methods enabled higher volumes of ice cream to be produced by pumping air into the mix, Regina stood her ground and stayed with the old-fashioned French pot method. All over the country, homespun ice cream parlors began going out of business, unable to compete with cheaper versions being mass produced and sold in grocery stores everywhere.

The Graeter’s story, in fact, could have ended in 1920. That’s when founder Louis Graeter was killed in an accident. Regina, 19 years younger, was left with two young sons and an ice cream business to run in the midst of the Spanish flu pandemic. She stubbornly soldiered on, opening a retail store in Hyde Park and then buying the manufacturing plant during the Great Depression.

She’s remained an inspiration to the succeeding generations. Rich Graeter and his cousins broke ground on a $12-million plant in Bond Hill during the Great Recession. The plant opened in 2010, now producing well over a million gallons of ice cream a year, enabling the company to expand the number of stores from 12 to 56 over 10 years and sell Graeter’s ice cream in 6,000 retail outlets across the country. But don’t expect that kind of growth to continue.

“That’s not in the cards,” Rich says. “I’ve seen other businesses grow themselves to death.” Growth will be managed, focusing on the Midwest and on its home market in Cincinnati. Along with the old-fashioned way to make ice cream, he believes he’s found the key to success: “The secret is not to be too greedy.”

While the three Graeters cousins hold “chief ” titles, the company has also looked outside for talent. Rich’s father hired Tom Kunzelman 19 years ago to run the manufacturing operation, and he’s now vice president of manufacturing. George Denman, a former sales exec for Dannon Yogurt, has managed national retail sales as VP of sales and marketing. Chief Financial Officer Craig Eten was recruited from Sunny Delight Beverage Co. “Everybody on the leadership team has a voice,” says Rich.

The fourth generation of Graeters, as well as the nonfamily leadership, know they’re custodians of a well-loved brand. “It’s our job to take care of it in our time and pass it on to the next generation,” says Rich. “Not just more family, but the next generation of team members and customers.”

Stephen Hightower literally grew up in his family’s business. When he was as young as 6, his parents would take him and his three siblings along to clean corporate offices around Middletown. Mom didn’t have a babysitter, so the kids were hauled along and helped wipe down chairs and baseboards.

The janitorial business owned by his father, Yudell, was run out of their home, with their books done on the kitchen table and business transacted in the living room. At an age when most teens are learning to drive, Stephen was running a truck crew that cleaned homes and businesses. By the time he was 18, he was negotiating contracts. “I would wear my work clothes at night, and during the day I would put on a suit and go out selling,” he says.

He bought his father’s business in 1981 and sold it in 1983, focusing on a new venture, Landmark Supply, selling industrial materials (drywall, lumber, nails, and so on) to commercial customers as well as to the state of Ohio.

In 1980, Ohio’s Minority Business Enterprise program was signed into law, mandating that state agencies set aside a certain percentage of their annual purchases for certified minority-owned businesses. “The state was buying everything from soup to nuts, literally,” Hightower says. “Everything the state set aside, we would go out and quote it.”

In 1982, the state set aside a portion of its fuel purchases, and Hightower, knowing little about the petroleum business, worked with a local supplier, Don Lykins, to bid on the contract. He won it. “My first contract was with the entire state of Ohio,” he says.

Three years later, the Cleveland office of energy giant BP was looking for a company to haul jet fuel to military bases in the region. He won that contract too, and it was the tipping point. The company name was changed from Landmark Supply to Hightowers Petroleum, concentrating on delivering fuel to a range of commercial clients.

A big break came while working with the region’s major gas and electric supplier, called Cinergy at the time. Hightowers had a small contract for several years with the utility to deliver one tank of fuel a month. When Cinergy joined a purchasing consortium with other utilities, Hightowers was able to offer an e-commerce solution for the group. That expanded its territory to what was then Cinergy’s three-state region in Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana. In 2006, Cinergy merged with North Carolina-based Duke Energy, and Hightowers Petroleum grew exponentially.

“That was the one company that gave us a footprint beyond Ohio,” says Hightower. “Now we’re doing business in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Florida.” And the company kept expanding from there, growing to become a national distributor for gasoline and diesel fuel for commercial fleets. Customers include GM, Ford, Kroger, Delta Air Lines, Duke Energy, and Cleveland-Cliffs (formerly AK Steel). “Those companies allowed us to have a national footprint,” says Hightower. “Today we deliver in every state in the U.S.”

At 65, he has the next generation primed to contribute. Son Stephen II is chief operating officer. Daughter Stephanie has been working in the business since high school and handles job bidding and contracts. Son Quincy runs Hi-Mark Construction Group, a unit working on wastewater treatment plants. Nephew Jason Hightower is the firm’s chief information officer. Two granddaughters also work in the business.

The elder Hightower recommends getting children involved in the family business at an early (maybe not as early as 6), so they can appreciate the ups and downs of running a firm. Succeeding generations, he says, may not have the same commitment to the enterprise that the founder does. “Most small businesses, when they’re growing, don’t necessarily have the best financial wherewithal,” he says. “You have a lot of challenges. When you’re going through a difficult building time, it’s probably not attractive to other family members to go through that grind you committed yourself to.”

Two other children work out of town outside the family business. Both Stephen II and Quincy worked for years in different endeavors before joining the Hightowers business. “Most family businesses need to be eased into,” Hightower says. “Getting the children involved at an early age is the key to them being comfortable to come back after going to school or doing whatever else they have to do.”

Indeed, developing the next generation of leadership is critical to family business success, says the Goering Center’s Butler. “There are very iconic founders and owners,” she says. “They can be difficult roles to fill.”

She often recommends that family businesses put together an independent board of advisers, maybe three people, who can provide an outside perspective. She also recommends writing a strategic plan and sharing it with the family. “Most business leaders could write down 80 percent of their plan right now,” she says. “It’s in their heads. But you should get it documented so you can communicate it to your family and your board.”

That kind of communication and planning will help the next generation not only survive what may come, but thrive.