Across the country today, many states, including Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio, are testing “trishare” programs that spread the financial burden of child care among workers, their employers, and government. In Hamilton County, a new program pays individuals while they train for jobs in child care. In state capitols and in Washington, D.C., organizations and individuals are lobbying for expanded government assistance for child care and higher wages for child care workers. These and many other efforts are attempting to ease a mounting crisis.

Child care costs are up nationally, with the average annual cost for an infant in child care running about $14,996 in Ohio, based on data collected by the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. That’s an almost 18 percent increase since 2018. Availability is down, stemming from a shortage of child care providers, and the result is a very real struggle for many working Americans to find safe, reliable, and affordable child care for little ones up until age 5.

Study after study is confirming that inadequate child care is bad for business, America’s workforce, and the nation’s economy, says Julianne Dunn, senior regional officer of the Cincinnati Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank Cleveland. Studies show that parents are cutting back working hours or dropping out of the workforce entirely in order to provide care themselves.

“I spend much of my time out in the district talking about the economy with business leaders,” says Dunn, sharing her personal views on the topic. “When I ask questions about their staffing needs or turnover rates, the conversation is increasingly turning to barriers to work like child care, transportation, and housing.”

The impact is so substantial, it’s now being tracked by a Parental Work Disruption Index created by professional services firm KPMG. Based on previously unpublished Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the index tracks losses in working hours, yearly and lifetime wages, and other data points related to child care access in the U.S.

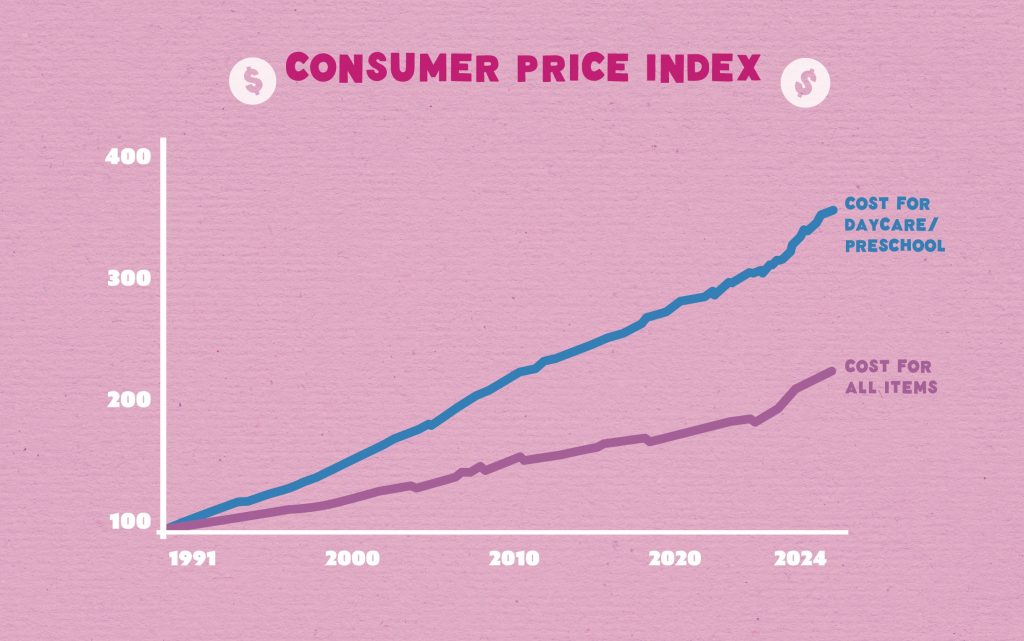

KPMG found that costs for daycare and preschool rose at nearly twice the pace of overall inflation between 1991 and 2024 and that between 1.2 to 1.5 million individuals—nearly 90 percent of them women—miss work in any given month because of child care needs. “This is on a clear upward trend compared to the pre-pandemic baseline,” says Dunn.

The child care conundrum is a double whammy for employers, says Charles Aull, executive director at the Center for Policy & Research at the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce, and warrants considerations for what can be done by all parties, including business leaders.

“Child care is both a current and a future workforce issue,” Aull says. “The more access to child care that’s out there, the more adults are going to be available to work. Investing in child care is making an investment in that future workforce, too, by increasing access to high-quality child care for those who will become your future workers.”

Illustration by Shelley Hanmo / Junonia Arts

Ten years ago, when Vanessa Freytag became president of Southwest Ohio’s nonprofit child care resource and referral agency, 4C for Children, she immediately recognized a problem. “I was a commercial banker earlier in my life,” she says. “Beyond health care, I would tell you child care is the most complicated and high-cost delivery industry that there is. Families can only afford so much, so the cost of delivery can in no way be scaled based on a family’s ability to pay.”

4C for Children directly helps roughly 1,000 local families a year find child care, maintains a searchable database to aid countless others, and provides training for regional child care workers. Through that work, Freytag has learned how multifaceted these businesses can be—providing child care services but also often some level of food service and perhaps transportation services.

Child care is a regulated industry that carries high labor costs for a reason, she says, because child-to-caretaker ratios must be kept low for safety reasons and to help every child receive adequate attention and interaction. “Children are like sponges from the ages of zero to 5,” she says. “Ninety-plus percent of the brain’s formation happens during that time. Yet we have underinvested in child care as a state and as a country.”

The situation starts with a wage problem, says Kyle Fee, a policy advisor for the Cleveland Fed who conducts applied research and outreach related to economic development, workforce development, and economic geography in the Fourth District, which includes Greater Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky.

The Cleveland Fed is a part of the Federal Reserve System, the central bank of the U.S. that’s mandated to set monetary policy with the intent of strengthening the nation’s economic performance. Promoting full employment is part of that mandate, Fee says, and child care has shown itself to be a big factor in maximizing participation in the U.S. workforce.

Child care providers are paid on average $14 an hour across the country, Fee says, earning the 10th lowest annual median wage ($28,520) out of 825 professions in 2022, just ahead of fast food counter workers and cashiers. There isn’t a state in the nation where a child care worker’s average pay provides a living wage for a single adult plus one child, Fee adds.

“Jobs at Amazon and other retail occupations are paying in the $18-$19 per hour range and sometimes also offering benefits,” he says. “When you think about the nature of the work in child care, you really have to have an interest and passion for children. The workforce is extremely important to the overall availability and quality of services that are offered.”

The child care sector is plagued by a turnover rate that’s 65 percent higher than the typical job, according to Fee’s research. All of this turmoil translates to fewer child care workers, leading to fewer available spots in classrooms, reduced numbers of classrooms, and the occasional closure of a child care center, Freytag says. 4C for Children conducted a survey in 2022 and 2023 that received a response from 40 percent of the region’s providers, which showed that the region had lost 2,500 child care seats since 2020, Freytag says.

“Local parents, if they have transportation, may be driving extraordinary lengths to a place that can provide child care,” she says. “Other families are having their children stay with neighbors or family, which maybe is a loving, caring setting, but in most cases those children are not getting the educational foundation they need.”

While there are public funds available to support child care for low-income households, the threshold is extremely low, Freytag says. Help is offered only to parents and guardians working or in school with a gross monthly household income equal to or less than 145 percent of the Federal Poverty Level. That works out to assistance being available for a family of four with a gross monthly income that is less than $3,770 a month, or $45,240 a year, says Judy Leonard, chief of the Child Care Section at Hamilton County Job and Family Services, which is responsible for distributing public funds.

Once a household qualifies for assistance, the family can continue to receive it until gross income exceeds 300 percent of the poverty level. “We don’t want child care being the astronomical cost that it is as you grow your income,” Leonard says. “We don’t want people to fall right off, because that isn’t going to help them sustain and become self-sufficient.”

Still, public assistance programs don’t cover the entire cost of child care, Freytag says. Parents must pay the rest.

In creating the new Parental Work Disruption Index, KPMG calls access to child care “a headwind to economic growth.” As “a source for unbiased economic intelligence,” KPMG Economics studies industries and topics such as child care, to “encourage fresh thinking, provide actionable insights, and improve strategic decision-making,” according to its website.

The firm’s research found that a lack of adequate child care disproportionately impacts women and low- to medium-income households but that men and higher income households are also seeing reduced productivity and lifetime earnings. Just one hour of work lost each week due to child care needs results in an annual loss of between $780 and $1,504 in income.

“Lack of access to child care results in millions of lost work hours,” the KPMG report says. Lost work hours include a decline in productivity and output from the workers who are absent as well as additional losses as coworkers pick up the slack. The report goes on to say “the blow to productivity and output compound over time, harming competitiveness. Together, they negatively affect the potential growth of the U.S. economy.”

In his work at the Kentucky Chamber, Aull hears from leaders in every industry who complain of workforce challenges in the tight labor market. While things have improved a bit since the pandemic, he warns this child care problem will not simply sort itself out. “Our population is getting older, and we’re having more and more folks enter into retirement,” says Aull. “We’re having fewer and fewer folks move into that working-age group and participate in the workforce, and so the workforce challenges we face are going to be playing out for a long time.”

When child care needs are ignored, the quality of care suffers even more, which can’t be downplayed, Freytag says. “Having problem-solving skills and being able to share and work successfully with another human are things you learn up through age 5,” she says. “If you ask HR folks, What are the most common reasons why you’re saying goodbye to a staff member? they’ll say things like, They didn’t show up to work on time. They didn’t work well with their coworkers. These are things children learn early on.”

New approaches are necessary, says Aull from the Kentucky Chamber, and the Commonwealth is trying several, including piloting the Employee Child Care Assistance Program to incentivize employers to contribute a stipend toward child care costs for their employees. The stipend will be matched by state funding. “ECCAP is focused heavily on improving affordability, especially for middle income families who don’t qualify for any government assistance,” says Aull. “It continues to show a lot of promise, but there are certain things that need to improve. Primarily, we need child care to exist for it to really work.”

That’s why Kentucky’s executive branch has also made the category of child care workers eligible for free child care, Aull says. As of January 2024, 3,811 child care workers were taking advantage of the benefit. “The real impetus behind that program was to create an incentive to encourage more folks to actually join the child care workforce,” Aull says.

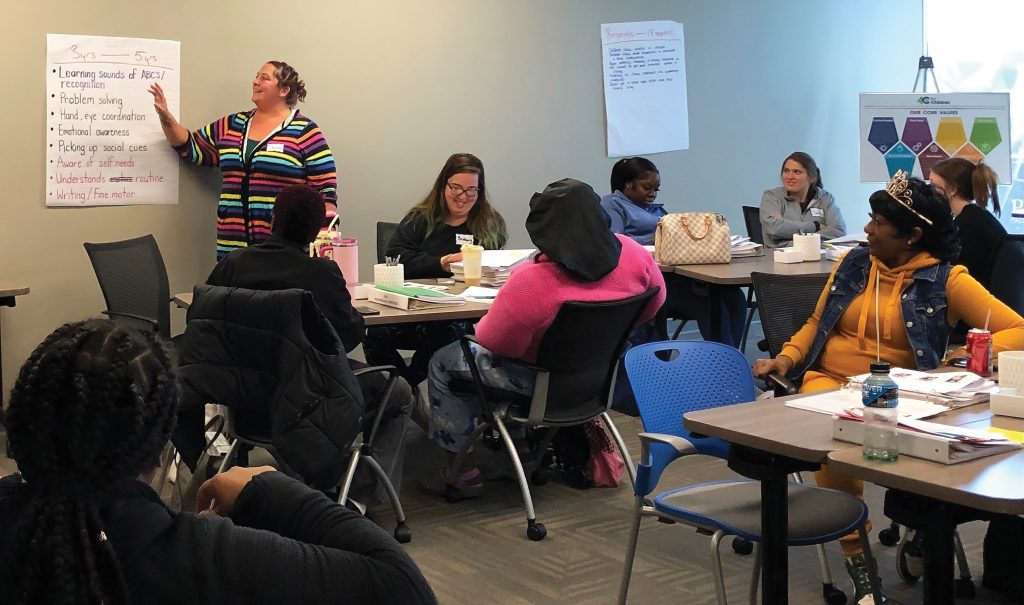

There are similar incentives in Hamilton County as well. 4C for Children created a program called Child Care Careers with funding support from partners such as the city of Cincinnati, the Hamilton County Board of Commissioners, and Cincinnati Preschool Promise. The program pays individuals as they train to become a child care provider; over its first 18 months, 135 individuals have completed the program, resulting in 93 new early childhood educators working in the region, Freytag says.

Organizations like 4C for Children are working hard to fill in the private employment gaps. Freytag is happy to report the opening or expansion of 76 child care businesses in the Cincinnati region during the 2023-2024 fiscal year, which added an additional 927 child care seats.

Several child care bills were introduced last year in Columbus, many from State Rep. Andrea White (R-Kettering). Three of her bills deal with child care tax credits for businesses and households. “It’s no secret that Ohio is experiencing a child care crisis right now, which in turn creates enormous challenges for businesses seeking to attract workers and sustain economic growth,” White said at a press conference last year. “Only 35 percent of our children are entering kindergarten ready to learn. That’s why we need to act now to help our communities partner together to solve this problem both for our families and for our businesses.”

4C for Children has helped some companies, including regional food manufacturer SugarCreek, create onsite child care centers for their workers, says Freytag. That makes sense for some businesses but not so much for others, she says, once again because child care is so challenging to provide. Freytag definitely supports child care stipends from employers.

“It is time for companies to really consider what is it actually costing them right now because they can’t fill positions or they lose their employees,” she says. “What would it mean if they could partially assist?”

At the least, Freytag asks that business leaders consider how much weight their voices carry inside the state capitol. “If our business community wants to change things in child care so that their employees have more access, more affordability, and higher quality, they need to add child care to the list when they’re advocating for the things they need in their own industries,” she says.

recruiting and training new child care workers.

In today’s tight labor market with its shrinking workforce participation rate, child care support goes a long way for recruiting and retention, Freytag says. The Modern Family Index found that nearly half of respondents (46 percent) put help paying for child care atop their wish lists of helpful benefits/supports, even above unlimited remote work (40 percent) and more flexible work hours (45 percent). Another source, the KinderCare Parent Confidence Report, released in 2023, found that 60 percent of parents said they would stay in their current jobs if offered subsidized child care.

Some child care programs, including ECCAP in Kentucky, operate using American Rescue Plan Act funding, which was divvied out to states to help mitigate economic downturn during the pandemic. But, as Aull says, much of that funding will dry up soon.

Child care has become such a contentious issue that the Kentucky Chamber’s Board of Directors recently elevated it to one of five pillars in its strategic plan and announced the Kentucky Collaborative on Child Care. The initiative pulls together a stakeholder group of business leaders, subject matter experts, HR professionals, economic developers, workforce professionals, state and local tax professionals, and more to decide how to proceed. “We’re doing this work through March to build consensus,” says Aull. “Then we’ll spend the next year trying to bring that vision to life.”

It’s time, he says, for business leaders to think long and hard on this topic and how they too can get involved. “There’s a huge return on investment,” Aull says. “Not only in the form of getting access to a larger qualified workforce today, but also making sure you have a trained workforce tomorrow.”