If a new indoor arena makes its way from concept to reality in Cincinnati, there’s a decent chance it will have to break with the naming convention of “Riverfront.” A feasibility study initiated by the Cincinnati Regional Chamber in May identifies a handful of sites that are potentially suited to be the home of a future new Cincinnati arena, and they aren’t along the Ohio River. In fact, a pre-conceived commitment to a riverfront location was not part of the study; its purpose was to perform due diligence in researching and vetting potential sites regardless of locale.

“We’re looking to deliver a common set of facts about what it would take, where are the places in this community it might be best situated, and what’s the opportunity a new arena brings to Cincinnati to attract the types of events and programming we know we’re missing out on today and we know bring economic life,” says Pete Metz, the Chamber’s vice president of civic and regional partnerships. “One thing we all agree on is that tourism lifts Cincinnati.”

The report includes a set of high-potential sites, with an analysis of each; an analysis of current booking and programming, with benchmarks from peer cities and a potential future state of booking and programming for the new arena; a range of construction costs; and a profit and loss analysis of the new venue. The study is a joint effort among such industry experts as Machete Group, Turner Group, Populous, and MSA Design. The steering committee includes Hamilton County, the city of Cincinnati, Visit Cincy, the Port, the Cincinnati Business Committee, the Cincinnati Regional Business Committee, and 3CDC among its core members.

“We’ve engaged folks around the community who work in the space, work in events and programming, or have an interest in real estate around these areas to make sure we get a clear understanding of the site analysis,” says Metz.

Visit Cincy, the region’s travel and tourism marketing organization, has been a major player in the arena proposal study—not a huge stretch, considering its current board chair is Jeff Berding, co-CEO of FC Cincinnati, second-year co-chair of the Cincinnati Regional Business Committee, and a vocal arena proponent.

“Our job is to promote this region and bring big events to this region, and yet we don’t have the necessary facilities,” says Berding, now in his fourth and final year as board chair of Visit Cincy. “The Duke Energy Convention Center was inadequate. The main convention hotel was poor. We tackled those issues as a region, and we now have a wonderful world-class headquarters hotel on its way, and the convention center is undergoing significant improvements, modernization, and site expansion. I felt it was time to tackle the city’s obsolete arena and to ask ourselves as a community, What can we do to address the shortcoming?”

[Illustration by Kenzo Hamazaki]

Cincinnati’s existing downtown arena, Heritage Bank Center, was built in 1975 as Riverfront Coliseum to complement nearby Riverfront Stadium. As their names implied, they were located on the river and housed a variety of sporting and entertainment events. Home to the minor league Cincinnati Cyclones hockey team, the arena building and its land are owned by Nederlander Entertainment.

The stadium, following several name changes of its own, was torn down to make way for Great American Ball Park after Hamilton County voters decided to fund new stadiums for both the Bengals and the Reds. GAPB now abuts the Heritage Bank Center and shares plaza walkways.

In 2022, the city of Cincinnati put out a request for proposal to redevelop the Town Center Garage on Central Parkway, which is also home to Cincinnati Public Radio (until its move to a new facility in Evanston in 2025) and WCET Channel 48. The site encompasses a total of 147,000 square feet. One of the RFP responses was a proposal by Visit Cincy and Machete Group to examine the site for its suitability as a brand-new arena.

The city decided to take the Town Center site off the redevelopment table earlier this year, and the Cincinnati Chamber took on the responsibility of conducting a full arena feasibility study. Machete, a sports and entertainment facility advisory firm based in Houston, was selected through a competitive RFP process to lead the study.

“We’ve been focused on developing arenas, stadiums, and mixed-use real estate around those facilities,” says Jerry Li, a consultant with Machete Group. “Our bread and butter is really overseeing the development of these types of venues. That’s how we got involved with TQL Stadium as well as the Mercy Health Training Center. The value we add is we come from that world and we know what it takes to operate those buildings and run sports teams, so we provide a unique perspective. We’re not traditional real estate developers.”

Machete has developed facilities for an assortment of sports teams, investors, and entities across the world, with U.S. arenas including the Barclays Center in Brooklyn, the Chase Center in San Francisco, and the Toyota Center in Houston. “We looked at, What are comparable arenas doing in terms of programming? What is Heritage Bank Center doing right now that a new arena could potentially do in terms of events and what does that mean in terms of profitability?” says Li. “We built out a conceptual financial model to demonstrate what revenue and expenses could potentially look like.”

Heritage Bank Center has undergone a variety of refreshes over the decades to accommodate the needs of a modern venue. But there are only so many retrofits that can happen before the original architecture has to be contended with.

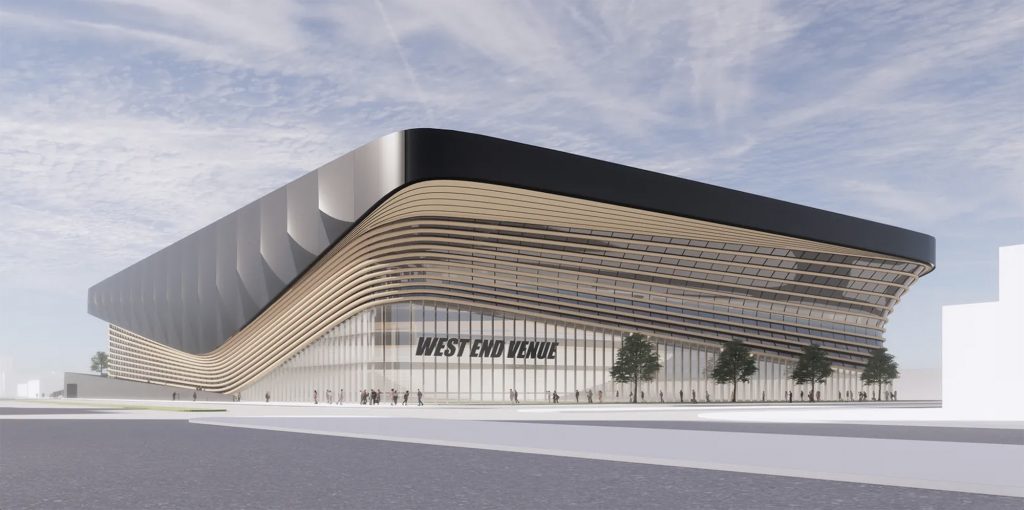

“When Riverfront Coliseum was built, it was a good arena for the time, but that was a different time,” says Bill Baker, managing partner with MSA Design. “Today that building is, at a minimum, about 60 percent of the total square footage that new arenas are. It should have wider concourses, a bigger back of house, and more loading docks. There’s a whole different customer experience expectation now with premium experiences, club experiences, and seating types from courtside and elevated suites to mid-bowl and bunker clubs. There are premium experiences where the players are walking in through the back tunnel under the floor and that’s a club now. That wasn’t the case in 1975 when the Coliseum was built.” MSA Design and Populous focused on the design and architectural piece in the feasibility study, suggesting high-level concepts since there isn’t a pre-determined site location.

Turner Construction examined building costs, and in addition to providing oversight Machete Group drilled into the business planning details. The group examined arenas in comparable markets for context, particularly those without major league anchor tenants such as NBA or NHL teams.

“While Heritage Bank Center has served us well over the years, it isn’t on par with the facilities you see in Louisville or Columbus or Cleveland or Kansas City,” says Berding. “The general public intuitively understands what we’re talking about, because they’re consumers of the games or shows appearing in those buildings and, like me, they sometimes travel to Columbus or Louisville to go to a concert and wonder, Why isn’t that coming to Cincinnati? At the same time, when you talk to business leaders who understand that major cultural events and major sporting events help drive economic activity—from hotel nights and support for downtown restaurants and small businesses—they see the role an arena plays in that.”

Metz says that Nederlander leadership sent a letter to the original Town Center Garage group saying the company would want the Cyclones to play in a new facility if one were built, which could eliminate the prospect of a new arena competing with the existing Heritage Bank Center. “So we’re operating under the assumption that we have a minor league hockey team as a possible tenant,” he says.

Heritage Bank Center occupies a total of about 350,000 square feet. The T-Mobile Center in Kansas City, Missouri, one of the closest to Cincinnati’s scope, encompasses 640,000 square feet. Nationwide Arena in Columbus is 740,000 square feet. Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis is 750,000 square feet.

The city of Kansas City opened T-Mobile Center (originally called Sprint Center) in 2007 without a major-league basketball or hockey tenant. Besides concerts, monster truck shows, and other events, the arena hosts lots of college basketball—from the Big 12 championships to men’s and women’s NCAA tournament rounds to one-off games involving area teams like the University of Kansas. The arena also is home to the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame.

“If we want to capitalize on the assets we have as a city, we need to have an arena that allows us to capture that business,” says Metz. “If you’re Taylor Swift and you’re bringing a 65,000-plus seat concert, we’ve got a stadium venue that works. What we do not have is a venue that works for the Bruce Springsteen arena show or the Childish Gambino concert that’s on tour right now or the two nights of Drake playing in three different Midwestern markets or the Death Cab for Cutie and Postal Service show. Those artists have chosen to book arena tours, and when they do they have a whole set of criteria they use to decide what venues to book. And right now, too often, we’re not on those tours because we don’t have a venue that can serve their needs.”

The Chamber convened a variety of stakeholders to provide input for the study, scheduling nearly 20 different interviews over the summer, including with Visit Cincy, the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, FC Cincinnati, Hard Rock Cafe, Nederlander, the Port, and the Ohio Department of Transportation, among others. “Anybody you could imagine who would have a vested interest in this project, we tried to touch,” says Li. “It became a long process, but I think we got a lot of valuable input, and we hope that all the stakeholders feel they were heard as part of this initial step of the process.”

The site criteria used in the study covered a gamut of hypotheticals in order to locate the highest potential locales in the region. “We looked at criteria like, How easy or hard would it be to acquire the site? Is the land area big enough to build an arena on it, and how easy is it for pedestrians and vehicles to access it? What amenities and public services are around the arena?” says Metz. “We looked at what is the site’s proximity to the region’s population, how easy or hard would it be for patrons to park, and how easy or hard would it be for them to take public transit. Finally, we studied whether the possible arena locations would catalyze additional off-site development.”

The study team found that the sweet spot for a site size-wise is a landmass of five-plus acres. “Below five, it gets a little tight,” says Baker. “But to six acres of the right shape and size is ideal, though it can’t be just a giant ribbon line. It’s got to be a big square. That gives you a good idea of a good site that can be made viable.”

The feasibility study looked at 15 sites across the region and narrowed its focus to three or four in the urban core, from the riverfront to Over-the-Rhine and the West End, with serious potential. The Heritage Bank Center site was one of those original 15.

Happening simultaneously to the study and arena discussion is the reconvening of the Greater Cincinnati Sports Commission, which will be charged with marketing the region to recruit sporting events (such as amateur youth and collegiate events), professional events, music and art shows, trade shows, and more. Berding will serve as chair of the newly formed commission.

“The Sports Commission will go out there and aggressively promote and try to attract those events into our new world-class arena,” he says. “I think the study shows that there’s a significant return on the investment in terms of visitors coming in and spending their dollars in our hotels and restaurants and in our retail shops, which of course helps grow the local economy and benefits everyone.”

What those benefits are in terms of dollars and cents are not necessarily being determined in this feasibility study. Metz sees the study is the first phase in a series of steps should a new arena be deemed feasible. The public has yet to be engaged, and the challenge of identifying funding remains.

“Ultimately, we’re not the folks who are going to build the arena,” he says. “What we’re trying to do here is create the landscape. There’s been so much conversation about a new arena in this town, but there hasn’t been a shared set of facts for everyone to make informed decisions. One of the first steps is to say, We’ve vetted the business model, vetted where you might put an arena, and vetted what a booking and programming strategy looks like, and here’s what we found. Then we can have a thoughtful conversation and make some decisions.”